Research Interests

Understanding biodiversity requires more than identifying the number of species on earth. We must also elucidate how species interactions govern the dynamics of communities, ecosystems, and species diversity. From mutualism to antagonism, interspecific interactions have been shown to be critical elements in the maintenance and promotion of biodiversity. As evolutionary ecologists, we use a broad combination of approaches including molecular phylogenetics, population genetics, experimental ecology, and field observations to understand the role that interspecific interactions play in creating diversity.

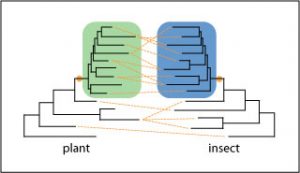

Coevolutionary Diversification & Insect Systematics

Specialization and coevolution are emphasized as the driving forces influencing patterns of speciation between two major groups of organisms in terrestrial communities: herbivorous insects and plants. Nearly 50 years ago, Ehrlich and Raven launched the study of coevolution by proposing a hypothesis to explain diversification in phytophagous insects and their hosts through reciprocal evolutionary change. Despite decades of research, it is still unclear whether coevolution is a driving force of diversification in interacting lineages. In addition to using manipulative field experiments, I am exploring this question by elucidating the systematics of two moth groups that have coevolved with their host plants.

Species Interactions & Plant Polyploidy

Plant polyploidy, or whole genome duplication, is an important diversifying force in plant evolution. Part of the success of polyploid lineages is due to the genetic consequences of genome duplication that can have cascading effects on phenotype, phenology, and habitat requirements. These differences between polyploids and their diploid progenitors may subsequently lead to changes in species interactions such as those with insect pollinators and herbivores. Although a few studies have examined how plant polyploidy impacts plant-insect interactions, we are still a long way from understanding how and why these associations shift as there does not seem to be a simple rule governing insect preference. Furthermore for a given plant species, there may be multiple, independently derived polyploid lineages that differ in genetic composition and also potentially in phenotype, phenology, or other traits. The consequences of multiple origins of polyploidy on species interactions remains relatively unexplored. My lab group is currently examining the effect of polyploidy on species interactions in the Pacific Northwest plant, Heuchera cylindrica.

Community Context of Mutualism

The importance of mutualisms in forming communities is evident- from the evolution of the eukaryotic cell to the growth of forests dependent on nitrogen fixing bacteria. Studies of mutualism, however, have only recently begun to expand beyond the pairwise interactions between mutualist species. Most work has been conducted in isolation of a broader biotic context, despite that this approach is unrealistic and may potentially be misleading. One research focus in my lab is to place mutualisms into their community context and understand how direct and indirect interactions with the surrounding community members affect the evolution of mutualists. This work has focused on the obligate pollination mutualism between yuccas and yucca moths and is being conducted with David Althoff. We are also using a synthetic mutualism to explore how manipulated community structure impacts the resiliance and persistence of mutualisms.

Exploitation of Mutualism

Mutualists trade a variety of commodities such as protection, food, and dispersal services in return for a service or commodity that is difficult or impossible for mutualists to obtain outside of the interaction. The presence of these commodities, however, gives ample opportunity for individuals to exploit mutualists by taking resources without providing services in return. These ‘cheaters’ may be opportunists from the community or they may evolve from within the mutualism itself. In the latter case, the evolution of cheating has been suggested to cause breakdown of the mutualism unless there are regulatory mechanisms to prevent overexploitation and extinction of the mutualists. While this may be an oversimplified view, the question of how mutualisms withstand the presence of cheaters remains central to the study of mutualism. One of the keys to understanding the dynamics of interspecific interactions is to determine the factors causing shifts in the outcome of an interaction along the continuum between antagonism and mutualism. I am currently using the yucca-yucca moth mutualism and a yeast model system to study how cheating evolves and persists in mutualisms.